In the aftermath of the tragic attacks in San Bernardino, an iPhone belonging to Syed Rizwan Farook, one of the assailants, propelled the previously cloistered debate on encryption into the mainstream.

The current legal clash between Silicon Valley and American law enforcement over encryption is hardly a new one. Apple and other American technology companies have been arguing these cases in the courts for several years. In most cases, Silicon Valley willingly complies with law enforcement’s requests. But from Apple’s perspective, this case is not like most cases.

Apple tallied a precedent-setting victory on Feb. 29 when a federal judge in New York rejected the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation’s request to unlock an iPhone seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. In its argument, the FBI and DEA cited the All Writs Act, a law originally passed in 1789, which authorizes the federal courts to “issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of the law.” This act is the same statute cited by the government in the case involving Farook’s iPhone, where the FBI is seeking to compel Apple to write code that overrides the device’s auto-delete security function — a project it estimates would cost over $100,000 — giving the FBI unlimited attempts to crack Farook’s passcode and access its data.

Encryption is ubiquitous and here to stay.

In response, the defense argues that the All Writs Act does not give the court the right to “conscript and commandeer” Apple into defeating its own encryption, thus making its customers’ “most confidential and personal information vulnerable to hackers, identify thieves, hostile foreign agents and unwarranted government surveillance.”

Cyber security is a huge public safety concern. On the one hand, the FBI is confronted with its current dilemma of gathering evidence in a terrorism case. On the other hand, Apple is considering the strategic implications of a world in which strong encryption is ubiquitous but only available to bad actors and not consumers of American products.

Protesters carry placards outside an Apple store on Feb. 23 in Boston. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

It is important for Americans to understand that this is not the first time technological advances have hindered the ability of law enforcement officers to do their jobs. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed into the law the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act. CALEA was a direct reaction to the telecommunication industry’s transition to digital telephone switches, which were often incompatible with the FBI’s traditional lawful wiretapping tools and techniques.

Not unlike the years preceding CALEA, we are once again at a crossroads where new technology is placing additional burdens on industry to assist law enforcement, and the people, through Congress, must again intervene in the best interest of the American public. Unlike with CALEA, though, security in this instance is measured not only by preserving law enforcement’s access to certain forms of evidence, but also combating the threats posed by criminals operating in cyberspace.

Likewise, privacy is measured by protection against unwarranted surveillance not just from our own government, but more likely from adversarial foreign governments like Russia and China who routinely capitalize on weak or non-existent encryption — not to mention protecting citizens of foreign authoritarian states who rely on American products to shield domestic surveillance.

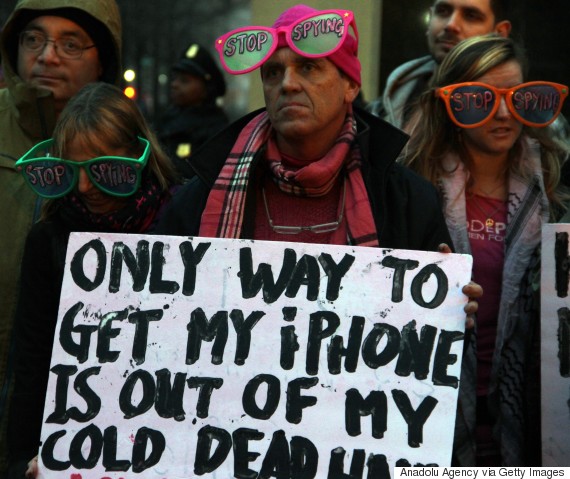

Protestors organized by Fight for the Future during a demonstration in support of Apple outside FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. on February 23. (Erkan Avci/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Moreover, the back-and-forth is also skewed by a lack of nuanced understanding of encryption itself, especially the difference between end-to-end, at rest and in-transit encryption. In fairness, anyone who talks about the FBI seeking a “backdoor” in the context of this case needs to spend more time understanding the technology involved.

Rather, the better argument in Apple’s favor considers the practical implications of a ruling against it. Consider the situation if the FBI does compel Apple to help crack Farook’s phone. What happens on the day after? Despite Apple’s weakened encryption, the technology will remain ubiquitous and readily accessible to terrorists and law-abiding citizens alike.

Most likely, the terrorists will react to the legal precedent by abandoning their use of American products for communications and data storage. As a result, the FBI still will not be able to access terrorist communications. Law enforcement will have the legal authority and technical means to gather evidence, but there will be no evidence to gather because their targets will have moved to the litany of apps and devices designed, developed and manufactured overseas. And a segment of Silicon Valley’s customers — perhaps less than most activists would lead you to believe — will boycott American-made products for embellished accusations of complicity with unwarranted surveillance by the American government.

Ultimately, it is for Congress to address both sides of the encryption issue without sacrificing security or privacy.

We’ve talked to law enforcement officers across this country and sympathize with their frustration. From local cops to state troopers to federal agents and U.S. attorneys, law enforcement officers want to do their job as they see it — gathering evidence to support their investigations and prosecuting criminals and terrorists. The law gives them this authority but in the digital age, encryption prevents them from accessing data on media that until now was readily available for a jury to consider.

Just as the FBI is seeking to compel a burdensome act on Apple, the gap between law enforcement’s authority and its investigative capacity also represents an unfair burden and a public safety risk. The Obama Administration’s proposal of a blue ribbon commission to look at this is timely, but it is only a first step.

Ultimately, it is for Congress — representing all of us — to address both sides of the coin in a manner that weighs the societal pros and cons of encryption and minimizes the burdens for all parties, including citizen users of American products. Congress must do so without sacrificing security or privacy in an age of new digital threats. This will require public hearings, much thought and carefully constructed legislation that will withstand court scrutiny.

Encryption is ubiquitous and here to stay. As a society, we must find the right balance between security and privacy and recognize that encryption is not just about privacy but about public safety as well.

Read the full post in TheWorldPost

Leave a Reply